Steve Byas the Great Depression Why It Started Continued and Ended

Fighting crime doesn't require new ideas or old ideas — but eternal ideas. New York City once understood this.

It's a conversation I'll never forget. My best friend and I were driving down to Manhattan to dine, in what had become a weekly ritual for us. We were discussing the crime in New York City, as many Big Apple residents no doubt did at that time, the mid-1990s. After all, as a result of the then-waning crack epidemic and turpitude-tolerant policies, criminality had been rampant and making headlines. I remember that we mentioned certain statistics, notably that the city had seen approximately 2,000 murders a year.

Our conversation would quickly become eerily and tragically ironic. As we drove along Bruckner Boulevard in the Bronx's Mott Haven section at about 8:40 p.m., we witnessed what turned out to be a high-profile murder, of a well-regarded Hispanic businessman and millionaire named Thomas Cuevas. We spent much of that night in a police station giving witness statements. In yet another irony, a week or two later my friend and I were driving the same route and his car broke down — within probably 30 feet of where the murder had occurred. While in the neighborhood subsequently getting his vehicle repaired, my friend heard grapevine information, which he later related to authorities, that might have aided their investigation. The perpetrators were eventually apprehended — it was at least partially an inside job.

What's also partially an inside job — perpetrated by politicians peddling bad policy (and, in fairness, the voters enabling them) — is high crime. After all, we know how crime can be quelled. In fact, this process' effectuation in NYC would transform the metropolis from a murder capital recording 2,262 homicides in 1990 to a remarkably safe big city with, in its best subsequent year, fewer than 300 killings. Yet it wasn't just homicide that dropped markedly (73 percent) between 1990 and 1999. Those years also saw burglary decline by 66 percent, assault by 40 percent, robbery by 67 percent, and vehicle thefts by 73 percent, reported the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2003.

As Professor George L. Kelling put it six years later in City Journal's "How New York Became Safe: The Full Story," the city's "drop in crime during the 1990s was correspondingly astonishing — indeed, 'one of the most remarkable stories in the history of urban crime,' according to University of California law professor Franklin Zimring. While other cities experienced major declines, none was as steep as New York's." Moreover, "Most of the criminologists' explanations for it — the economy, changing drug-use patterns, demographic changes — have not withstood scrutiny," Kelling continued. So what changed?

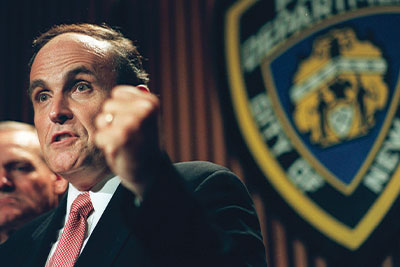

The name Rudolph Giuliani, the man who became Gotham's mayor in January 1994, may come to mind. Even Michael Tomasky, writing for the liberal New York magazine in 2008, had to characterize Giuliani positively as a "tornado that had just hit town." "By the end of Giuliani's first year, the city was a visibly different place," Tomasky admitted, "made safe, Toronto-ized…. Lots of forces combined to change that, but the biggest force of all was Rudy." This line reflects reality: Much as how Trump represents the larger MAGA phenomenon, Giuliani became the face and facilitator of a movement that preceded his tenure.

America's mayor: Rudy Giuliani ran as a tough-on-crime mayoral candidate in 1993 — and he delivered. Becoming the face and facilitator of a law-and-order movement that preceded his tenure, he became the main author of what one law professor called "one of the most remarkable stories in the history of urban crime." (AP Images)

Professor Kelling introduced this story, writing that as NYC convulsed with criminality,

an idea began to emerge that would one day restore the city. Nathan Glazer first gave it voice in a 1979 Public Interest article, "On Subway Graffiti in New York," arguing that graffitists, other disorderly persons, and criminals "who rob, rape, assault, and murder passengers ... are part of one world of uncontrollable predators." For Glazer, a government's inability to control even a minor crime like graffiti signaled to citizens that it certainly couldn't handle more serious ones. Disorder, therefore, was creating a crisis that threatened all segments of urban life. In 1982, James Q. Wilson and I elaborated on this idea, linking disorder to serious crime in an Atlantic story called "Broken Windows."…

Yet it wasn't just intellectuals who were starting to study disorder and minor crimes. Policymakers like Deputy Mayor Herb Sturz and private-sector leaders like Gerald Schoenfeld, longtime chairman of the Shubert Organization, believed that disorderly conditions — aggressive panhandling, prostitution, scams, drugs — threatened the economy of Times Square. Under Sturz's leadership, and with money from the Fund for the City of New York, the NYPD developed Operation Crossroads in the late 1970s. The project focused on minor offenses in the Times Square area; urged police to develop high-visibility, low-arrest tactics [note: de-emphasizing arrests was not a good idea]; and attempted to measure police performance by counting instances of disorderly behavior.

Something should be mentioned here about the aforementioned notion, put forth by soft-on-crime naysayers, that an improved economy could be credited for the '90s crime decline. It's not just that the economy was booming throughout the Reagan years and somewhat beyond ('81-'90); it's not just how there's evidence that crime declined during our country's worst economic disaster, the Great Depression. It's also this: Domestic tranquility facilitates a sound economy. After all, if businesses will be subject to continual robbery and shoplifting — and sometimes extortion by organized criminal elements — and must spend much on security, it amounts to an unfriendly business environment that hampers commerce (think Detroit).

Kelling informs that, despite bearing some fruit, Operation Crossroads was eventually abandoned. Yet there'd be other, similar efforts, such as attempts to clean up Manhattan's Bryant Park; an '84 program aimed at eliminating subway graffiti; an '88 plan to bring order to the Grand Central Terminal area, which was accompanied by 32 more "Business Improvement Districts" that effected similar approaches; and an '89 transit police crackdown on "minor" subway offenses (e.g., fare beating), which in the early '90s was replicated at Penn Station and Grand Central.

Neighborhood organizations also applied pressure to restore order, Kelling tells us, and the judiciary did its part in '93 with the establishment of the Midtown Community Court, which expeditiously handled minor offenders. "In sum, a diverse set of organizations in the city — pursuing their own interests and using various tactics and programs — all began trying to restore order to their domains," Keller writes.

As this effort crystallized, it began translating into political will. This manifested itself notably when Ray Kelly was appointed NYC's 37th police commissioner on October 16, 1992 by liberal mayor David Dinkins. Kelly "helped spur the [crime] decline in New York by instituting the Safe Streets, Safe City program and putting thousands more cops on the streets. (In 1990, after the shocking murder of a tourist in the subway, Mayor Dinkins got funding for an additional 6000 cops with an income tax surcharge)," related the Gotham Gazette's Julia Vitullo-Martin in 2001. "Kelly believed in Broken Windows policing — taking care of minor signs of disorder so they don't become major. He initiated the campaign against the squeegee men," for example.

CompStat

Along with the political will, however, something else was crystallizing — it was an innovation in policing. Study.com presented its story, writing, "Imagine you're going to the grocery store for your monthly shopping. When you get to the store, there are no signs above or at the end of the aisle to show you where things are. While you might get lucky and find some things by guessing, you would most likely waste a lot of time walking up and down the aisles hoping to find what you need." "This is similar to what police work was like," the site continued, before something called "CompStat."

Originating under the direction of a NYC transit cop named Jack Maple as "Charts of the Future," this system initially just tracked crime through pins stuck in maps. It was later re-christened "Compstat," a name that "stands for 'Computer Statistics' dealing specifically with crime," Study.com also informs. "Most companies throughout the world have used computer-generated statistics for years to track how successful their company is. However, it wasn't until 1994, when CompStat was developed, that police departments around the country started doing the same thing to help track how successful they were in fighting crime." It was that year that Giuliani became mayor and wisely appointed William Bratton NYPD commissioner. Bratton, who'd been transit police chief since '90, had been impressed with underling Maple and brought him to the NYPD, making him deputy police commissioner; it was then that his "Charts" system was rebranded CompStat.

CompStat used troves of data and computer-generated statistics to predict where crime would occur, deployed resources based on this information, set goals for tactics, and then provided for "relentless follow-up and assessment, where you can look at what's working and what's not and have the flexibility to change," as law-enforcement technology company CivicEye puts it.

CompStat also became a means to implement the then-new Broken Windows theory, New York magazine Intelligencer's Chris Smith reported in 2018. "Developed by [the earlier mentioned] criminologists James Q. Wilson and George Kelling, a Bratton adviser ... Broken Windows held that ignoring small violations of the law, or quality-of-life offenses, led to larger crimes and to increasing disorder," Smith continued. "Maple didn't read the academics' theories until he'd left the NYPD, but he'd been practicing their precepts years earlier, in the subway. Cracking down on turnstile jumpers, he and Bratton found, had a multiplier effect, depressing robberies and assaults. Crucially, the gains were not simply a result of arresting larger numbers of fare-beaters, but in following up on the arrests and discovering that many of those in custody had outstanding warrants for more serious crimes."

Pre-crime: Emulating the business world, which had long used computer-generated statistics to measure success, in 1994 the NYPD introduced "CompStat." It enabled police to not just react to crime, but predict where it would occur — and determine how best to thwart it. (AP Images)

The bottom line is that no "New York invention, arguably, has saved more lives in the past 24 years" than has CompStat, Smith also tells us. It had "helped drive down the city's crime rates to historic lows and revolutionized policing around the world: Los Angeles, London, and Paris use a form of CompStat. Baltimore has CitiStat; New Orleans has BlightStat. Bur-lington, Vermont, runs CommunityStat, to battle the opioid epidemic."

As a result of all the above efforts, NYC transitioned from being a crime capital in 1990 to, just a handful of years later, "the safest large city in the nation," wrote the Los Angeles Times in 1997, citing FBI statistics. Giuliani deserves much credit, too. Oh, he didn't originate the ideas in question, but that's not what good leaders generally do, anyway. Rather, they do what Giuliani did: exercise enough wisdom to choose the right subordinates and embrace what works.

Unlike his predecessor, Dinkins, who was late responding to the crime crisis and perhaps did so driven by reelection concerns, Giuliani campaigned as a crime fighter and followed through. He sank his teeth into the effort and leaned heavily into Broken Windows, CompStat, and anything else lawful and effective. In contrast, President Bill Clinton's left-wing administration was at the time serving up ideas such as "Midnight Basketball" (in the vain hope that youths out when they shouldn't be, in the morning's wee hours, will shoot hoops and not each other).

Giuliani's policies were continued by the subsequent Michael Bloomberg administration and even into leftist Mayor Bill de Blasio's tenure (the latter hired Bratton as his first police commissioner), which is perhaps why NYC recorded its lowest homicide rate in 2017. In recent years, however, the corrosive effects of left-wing governance (such as de Blasio's), liberal district attorneys more focused on "equity" than justice and more concerned with criminals' "rights" than criminals' wrongs, no-cash-bail laws, and public officials implementing a new Broken Windows theory (let BLM/Antifa rioters break as many windows — and heads and laws — as they want until power is achieved), have led to a crime explosion. Thus should something be emphasized:

None of this is rocket science.

While common-sense-oriented innovations such as CompStat are welcome, man has long known how to minimize crime. Just consider that the National Bureau of Economic Research writes, citing a study and simple truth, that the "police measure that most consistently reduces crime is the arrest rate of those involved in crime." Put more cops on the streets, avoid handcuffing them with unreasonable "rules of engagement," arrest more perpetrators, choose prosecutors who'll actually prosecute (criminals, not those practicing self-defense), have a justice system that operates expeditiously and administers punishment sufficient to deter law-breaking, and lock more miscreants up, and crime will go down. For a recent example, note that tiny El Salvador, not long ago known as "the murder capital of the world," has seen homicides drop from 6,656 in 2015 to 530 in 2022 (as of September 22). Not surprisingly, the nation has been locking up thousands more criminals — and should now have completed a new prison designed to accommodate 40,000 gang members.

Unfortunately, though, "The only thing that we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history," observed German philosopher Georg Hegel. Favoring "rehabilitation" over punishment — forgetting that proper punishment is rehabilitation — was in fashion in the 1960s and '70s; more criminals were put back on the streets and crime proliferated. In the '90s, we locked up more miscreants again, but perhaps people have had it good enough for long enough that they're willing to entertain an old mistake masquerading as a new idea. So the turnstile-justice/higher-crime cycle is repeating itself. Why, Democrat John Fetterman, U.S. Senate candidate from Pennsylvania, advocated last year releasing all second-degree murderers from his state's prisons — and he's ahead in the polls.

Remember, too, that all this is happening during a time of increasing moral decay, in which people are becoming more barbaric. And loosening external restraints on bad behavior while internal restraints are also weakening is a recipe for disaster. Of course, the deeper solution is to strengthen those internal restraints by returning to God and His virtue. In the meantime, however, when the patient is screaming in pain, symptomatic treatment is the godly approach.

Source: https://thenewamerican.com/magazine/tna3820/page/242787/

Post a Comment for "Steve Byas the Great Depression Why It Started Continued and Ended"